Therapeutic Benefits of Yoga for Children with Autism

by Carlos Villanueva, RYT 200, RPYT

With no known singular cause and at a prevalence of about 1 in 68 children in the United States, autism continues to be an important public health concern for children. Autism can be describes a group of complex related neurodevelopmental disorders. The effects of autism on learning and functioning can range from mild to severe. These differences can cause confusion, frustration, and anxiety that is expressed in a variety of unexpected ways. Most children with Autism or Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) have sensory-processing disorders. Sensory processing disorder is a condition in which the brain has trouble receiving and responding to information that comes in through the senses. Yoga poses, breathing strategies, and visualization strategies, when taught in an accessible way, can support children with autism in expressing and releasing difficult emotions, sensory integration, self-regulation, social and communications skills, reducing anxiety, and an overall increase in self-esteem and self-acceptance. For a yoga therapist, it is useful to obtain extensive information about the child’s history and predisposition. Knowing the child’s preferences, learning styles, strengths, and limitations is imperative when creating a yoga therapy session. When developing a program for children with autism, it is important to see the whole child, and to meet the child where they are at. The use of daily yoga interventions can have a significant impact on key classroom behaviors among children with ASD.

History of Autism

When you are around people with children on the spectrum the first thing they are likely to tell you is “If you’ve met one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism.” This is because every child with autism is completely different from the next. Every child has their own set of complex neurodevelopmental disorders and each child is completely different from the next in the way they understand the world and cope with it. You might have noticed that the symbol for autism is puzzle piece. The puzzle as sign of autism dates back to 1963 created by Gerald Gasson parent and board member for the national Autistic Society he adopted the logo because it didn’t look like any other imaged used for charitable or commercial use. Since then the sign has gone through many variations until the current day. Some people do not like the puzzle piece as a symbol for the condition because it implies a mystery or something that needs to be put together. Others like the symbol because it symbolizes how there’s no one therapy that works for everyone and sometimes it’s a whole puzzle of therapies that actually work.

The term autism comes from the Greek word for self, “autos,” a condition in which a person seems quite literally to live in his or her own world. Two physicians described autism and gave it the same name nearly simultaneously in the mid 1940s. One of them was the Austrian Hans Asperger for whom a form of high-functioning autism, Asperger’s syndrome, is named (P. Collins, 2011). During WWII Hans Asperger ran a clinic and school that work with autistic children and he name his clinical group “autistic psychopathy." A few years later, Nazi Germany took over his facility and it was eventually bombed and destroyed but it worth noting that Hans Asperger worked tireless to make sure the facility stayed open for as long as possible. He even went as far to try to convince the Nazis regime that children with autism could be taught to be good code-breakers for the Third Reich. Dr. Leo Kanner, has since been credited for discovering autism and being the first person to write an English text about it (Silberman, 2016). Dr Kenner was also Austrian–American and called the condition “early infantile autism." It is likely that Leo Kenner knew of Asperger research since one of Asperger assistants ended up working with Dr. Kenner in the United States.

There are four main sub-types of autism recognized within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition 1952, published by the American Psychiatric Association.

- Autistic Disorder, also known as autism, childhood autism, early infantile autism, Kanner's syndrome or infantile psychosis

- Asperger Syndrome, also known as Asperger's disorder or simply Asperger's

- Childhood Disintegrative Disorder, also known as CDD, dementia infantalis, disintegrative psychosis or Heller's syndrome

- Pervasive Developmental Disorder (Not Otherwise Specified), also known as PDD (NOS) or atypical autism.

The terms "refrigerator mother" and "refrigerator parents" were coined around 1950 as a label for mothers and parents of children diagnosed with autism or schizophrenia. When Leo Kanner first identified autism in 1943, he noted the lack of warmth among the parents of autistic children. Parents, particularly mothers, were often blamed for their children's atypical behavior, which included rigid rituals, speech difficulty, and self-isolation. Kanner later rejected the "refrigerator mother" theory, instead focusing on brain mechanisms.

In the 1970s, a cognitive psychologist in London named Lorna Wing had an autistic daughter and was very aware of the challenges that were faced by families with autistic children in search of services. She and a research assistant did a survey in a London suburb to look for autistic children in the community and what they found was that there were many more of cases of Autism undiagnosed. When Lorna Wing stumbled across a reference to Hans Asperger's paper she immediately saw that what Asperger had seen in Vienna was what she was seeing in London in the 1970s. Lorna Wing quietly worked with the people who are designing the next edition of the DSM to broaden the scope of the diagnosis and so in a sense she swapped out Connors criteria for Asperger’s criteria and almost immediately the number of diagnoses started soaring. The fifth edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5, published in May 2013, eliminated the four sub-types listed above by dissolving them into one diagnosis called Autism Spectrum Disorder. According to the American Psychological Association, this represents an effort to more accurately diagnose all individuals showing the signs of autism. At present, the term 'autism' is sometimes used interchangeably with the term 'autism spectrum disorders' to mean any or all of the different forms of ASD. It is also sometimes used interchangeably with the term 'autistic disorder (Types of Autism, 2016).

Rett syndrome is no longer considered to be a sub-type of autism, although individuals with Rett syndrome may display autistic-like symptoms. Rett syndrome until a few years ago was thought to be a behavioral disorder. The genetic change was identified and moved from autism spectrum disorder into its own category. This scenario will happen a lot in the next few years, where a genetic cause is identified and it will move away from autism spectrum disorder (LITZY, 072: Tracy Stackhouse, OT, 2012). Similarly, Fragile X is genetically defined disorder that is caused a change in the chromosome that is passed in families and leads to a set of characteristics that can include some behaviors that look like autism.

In 1998, Andrew Wakefield was a gastroenterologist who released an instantly controversial paper blaming a certain form of autism on the MMR vaccine. This publication was pick-up worldwide and panic about vaccines grew almost overnight. The vaccination recommendation of the MMR vaccine coincides with the age of when a child first starts to exhibit the signs of Autism. The Wakefield paper has since retracted and discredited.

What is Autism?

ASD is described as a group of complex related neurodevelopmental disorders. Hallmarks of ASD include deficits in social communication and interaction as well as restricted, repetitive behaviors, activities, or interests. ASD occurs in all racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups. (Kuehn, 2016). Boys are four times more likely to have the condition, but clinicians often miss or overlook symptoms in girls, who are frequently on the less disabling end of the spectrum (Zwillich, 2016). Autism tends to run in family. On some level autism is thought to be genetic. The current thinking is that there are a variety of genes that dormant waiting to be trigger. At this time we don’t know what those triggers are. It could be prenatal, environmental, or toxins (LITZY, 072: Tracy Stackhouse, OT, 2012).

A number of secondary medical and behavioral issues frequently occur with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). These “co-morbid conditions” include anxiety, depression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), gastrointestinal (GI) problems, sleep disturbances and epilepsy (Speaks, Autism Speaks ) We also know that autism causes discrepancies or differences in the way information is processed, affecting the ability to:

- Understand and use language to interact and communicate with people

- Understand and relate in typical ways to people, events and objects in environment

- Understand and respond to sensory stimuli-pain, hearing etc. (Goldberg, 2013, p. 14).

The treatments for autism include applied behavior analysis, medications, occupational therapy, physical therapy and speech-language therapy. Medications are used to treat behaviors and symptoms including aggression, anxiety, attention problems, hyperactivity, mood swings and sleep issues, according to the NIH (Boghani, 2012).

Understanding Autism

The effects of autism on learning and functioning can range from mild to severe. These differences can cause confusion, frustration, and anxiety that is expressed in a variety of unexpected ways, such as withdrawing engaging unusual repetitive behaviors and occasionally, in extreme situations, by aggression and/ or self-injury (Goldberg, 2013, p. 14). It is widely accepted that autism is a neurological disorder, but the exact cause or causes are not known. There is now a body of research that has identified specific regions and systems of the brain that are abnormal in brain imaging and autopsy studies of individuals with autism spectrum. The cerebrum cortex, along with five other regions have been identified including the limbic system, corpus callosum, basal ganglia, brainstem and cerebellum. These regions are interconnected through systems in the brain that regulates emotion, attention, communication and language, cognition sensory response and movement. Although we may not know the cause of autism these features are associated with abnormal connectivity in these brain regions. Recent brain imaging research has shown an abnormal increasing brain volume in the first few years of a child life with autism. Discovering the genetic, cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying this brain overgrowth is the focus of current research.

Children with autism are believed to lack “theory of mind” that is , they may not understand that other people experience different thoughts and perceptions from their own. This concept has been used to explain lack of empathy and awkwardness in social interactions (Goldberg, 2013, p. 76). Simon Baron Cohen was the first person to notice theory of mind in his now famous experiments. He ran three experiments with autistic children, in which he asked if autistic children had a concept of self, if they perceive what others are looking at, and if they can appreciate what other are thinking. He discover that autistic children do have a concept of self and ability to appreciate what other are seeing but lack the ability to appreciate what others were thinking. On a interesting note, he noticed that when he tested children with down syndrome they did have the ability to appreciate what other were thinking.

Sensory Processing Disorder

Self-regulation is the ability to self-organize to control ones activity level and state of alertness as well as one’s emotional, mental or physical responses to sensation. It greatly impacts a child’s interaction with their environment and the world around them. Self regulates impacts: social skills, attention, mood, energy level, learning, behavior. (Hardy, Montreal International Symposium on Therapeutic Yoga, 2017)

Sensory processing disorder formerly known as Sensory Integration Syndrome is a condition in which the brain has trouble receiving and responding to information that comes in through the senses. A child who has sensory processing disorder or sensory integration difficulties perceives/takes in sensory information differently—they detect the sensory information, however the sensory information gets mixed up in their brain, therefore their responses can be inappropriate, unexpected and often misinterpreted (Hardy, Montreal International Symposium on Therapeutic Yoga, 2017). Some children with sensory processing disorder are oversensitive to things in their environment. Common sounds may be painful or overwhelming. The light touch of a shirt may chafe the skin. Sensory processing disorder may affect one sense, like hearing, touch, or taste or it may affect multiple senses. Children can be over-or under-responsive to the sensory input (MD, 2017).

According to STAR institute, at least three-quarters of children with ASD have significant symptoms of sensory processing disorder (Hardy, Montreal International Symposium on Therapeutic Yoga, 2017).

Most children with ASD have sensory-processing disorders. Although visual-spatial skills may be more advanced, other sensory responses, such as those to touch and auditory input, suggest poor modulation. Greenspan and Wieder (1997) estimated that 39% of children with ASD are under reactive to sensation, 20% are hypersensitive, and 36% show a mixed pattern of hypersensitivity and hyposensitivity (Case-Smith, 2008). It is important to note that children in the autism spectrum have some type of sensory processing disorder. However, children that have sensory processing disorder doesn’t necessary mean that they have autism. Many children with autism report heightened sensory perception. They may be acutely aware of sounds or of people or objects touching their skin. Researchers have theorized that this feeling of sensory overload might make social situations overwhelming and challenging to navigate (Wright, 2016). Children with Autism may need sensory processing therapy or sensory integration therapy. Sensory integration (SI) therapy identifies such disruptions and uses a variety of techniques that improve how the brain interprets and integrates this information. Occupational therapists often use sensory integration. Other times it is delivered as a stand-alone therapy (Speaks, Autism Speaks.org, 2017). When a child with autism wants to give a hug to another child, he might tackle the other child. When the child is moving through space he lacks ability to measure how his physical body is moving in space (LITZY, 058: Occupational Therapist Rayne Pratt, 2012). Sensory integration (SI) therapy will often include: Supine flexion, prone extension, crawling, log rolling, vestibular activities (in different swings), crashing, hopping off high platforms (LITZY, 121: Sensory Processing Disorder w/ Alexander Lopiccolo, COTA, 2014).

The Five Senses

Touch

For some children with sensory challenges, touch can be extremely unpleasant. Temple Grandin, an expert on animal handling, is on the autism spectrum. She describes the evolution of her relationship with touch in her book thinking in pictures.” The application of physical pressure has similar effects on the people and animals. Pressure reduces touch sensitivity … Slow application of pressure is the most calming.

Grandin describes her own discomfort at being touched until she invented her squeeze machine, an apparatus that applied steady firm pressure to her entire body under her control. After learning to experience comfort in touch, she was finally able to pet her family cat, who had previously run from her due to rough handling. She also learned to tolerate touch from others. “It was difficult for me to understand the idea of kindness until I had been soothed myself … I believed that the brain needs to receive comforting sensory input. Gentle touch teaches kindness. “

Most children find comfort in touch, it makes them feel safe and cared for. Stroking the skin releases endorphins and reduces stress, according to Dacher Keltner. “Touching instills trust and spreads goodwill … through the release of opioids and oxytocin. They trigger the activation of the vagus nerve, the nerve bundle in the body devoted to trust and social connection…and shift the …HPA axis activity-to more peaceful settings.”

Because the responses to touch are so varied, it’s important to secure permission before touching a child. For touch to retain its soothing properties, it must be something that child chooses and feels the right to reject (Goldberg, 2013, p. 67).

Tactile defensiveness makes contact sports such as soccer and football intolerable for some children. Competitive play requires a great deal of social skill, a challenge for many children on the autism spectrum. Children with special needs often experience greater success with supportive activities. Loud, unstructured activities in gyms or playgrounds can be overwhelming. Care should be taken to address one sensory modality at a time. Extreme sensitivity may result in outburst or increased repetitive behaviors. Keeping exercise periods short with planned transitions is helpful for those with attention deficits. Recommended physical activities for children with ASD include “rhythmic, large muscle activities that are continuous in nature” (Goldberg, 2013, p. 55).

Auditory Processing

The brain does not accurately interpret and respond to auditory information and a child could be Hypersensitivity/Hyposensitivity to sound. When a child with autism is hyposensitive they are likely to make noise frequently, for example, humming, singing, yelling, etc. (they are trying to get more auditory input ). For this type of child, activities such as chanting , rhythmic clapping, bee breath, singing bowl would be helpful. On the other hand, when children are hypersensitive they are likely to cover their ears to avoid sounds or environment (Hardy, Montreal International Symposium on Therapeutic Yoga, 2017).

Olfactory System

The olfactory system is how we process information about the odors around us and discriminate between dangerous, pleasant , strong, and foul smells. A child with autism may have hypersensitivity/hyposensitivity to odors. Essential oils such lavender (calming) while peppermint can be (invigorating). It is best to dilute any oils use cotton balls to avoid any skin sensitivities (Hardy, Montreal International Symposium on Therapeutic Yoga, 2017).

Gustatory/Oral motor Processing

Sensory processing disorder can also affect the taste or gustatory system. A child with autism can be hypersensitive or hyposensitive to taste. This type of child will likely be a picky eater or eat things that are not food. The child may be show intolerance to certain food or texture and smells or lack the ability to taste correctly. Activities such as blowing bubbles or straw breathing can be helpful (Hardy, Montreal International Symposium on Therapeutic Yoga, 2017).

The Two Hidden Senses

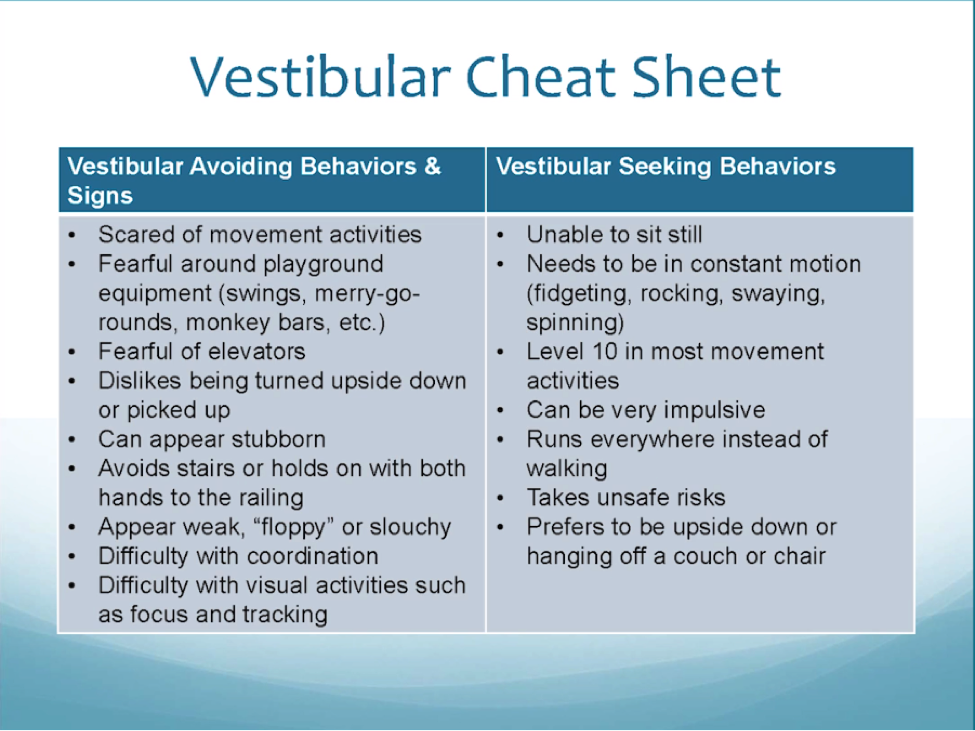

Vestibular and Proprioception System

The vestibular receptors located in the inner ear, respond when a person moves quickly in a circular direction. These receptors help maintain balance by coordinating motions of the eyes and head. The vestibular system also activates postural reflexes throughout the body to keep it in balance. AJ Ayres points out that many children with autism seek the sensation of spinning, without experiencing the typical dizziness response, suggesting that “some vestibular input is not being registered” (Goldberg, 2013, p. 25). In addition to a sense of balance vestibular input affects gravitational security (Hardy, Montreal International Symposium on Therapeutic Yoga, 2017).

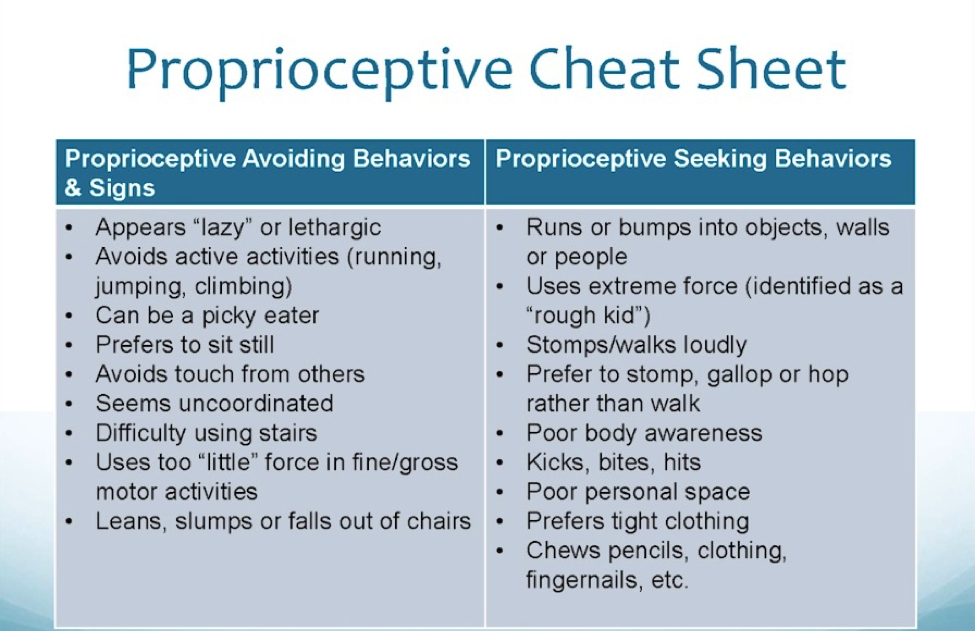

Proprioceptive senses provide information to the brain by way of our joints and muscles, the position of the body in space and what each part of the body is doing (kinesthesia). Autistic children often have spatial problems, of which telling left from their right is only one of the aspects (Davide-Rivera, 2012).

How Yoga Therapy Benefits Children with Autism

There are many ways yoga therapy can be beneficial to children with autism. Many children with autism struggle with language-processing difficulties, identifying and communicating difficult or uncomfortable emotions, sensory-integration challenges, and knowing how to self-regulate their physical and emotional states. Children with autism also may struggle with anxiety and obsessive thinking. Yoga poses, breathing strategies, and visualization strategies, when taught in an accessible way, can support children with autism in expressing and releasing difficult emotions, sensory integration, self-regulation, social and communications skills, reducing anxiety, and an overall increase in self-esteem and self-acceptance. Along with the many benefits listed, yoga also has many physical and mental benefits that support improved motor coordination, fine/gross motor skills, strength, flexibility, sleep, digestion, memory, focus, and concentration. These are all areas that can be a struggle for children with autism (Ashworth, 2016). Many children with special needs are victimized by their own minds. Thoughts, feelings, sensations bombard them continually, increasing their levels of stress and forcing them into flight or flight response. Improving focus in posture is a preparatory step toward meditation. Regulating the breathing, practicing quiet relaxation and turning inward for mindfulness practices are additional ways to introduce children with special needs to the process of stilling the mind. Children with autism spectrum, ADD, ADHD, SPD often lack of core stability and Yoga Therapy can easily be incorporated to address core issues. (LITZY, 121: Sensory Processing Disorder w/ Alexander Lopiccolo, COTA, 2014).

The results of one study published in the International Journal of Yoga Therapy showed an improvement in imitation skills. The study indicated that yoga may offer benefits as an effective tool to increase imitation, cognitive skills and social-communicative behaviors in children with ASD. In addition, children exhibited increased skills in eye contact, sitting tolerance, non-verbal communication and receptive communication skills (Radhakrishna, S., 2010). The ability to understand ones actions and imitate those actions are directly correlated to the development of social-communication skills. When practicing yoga poses and breathing strategies, children learn the poses and breathing through imitating the actions and behaviors of the adult. This also supports children’s ability to sustain joint attention, something that can be a challenge for children with ASD. Visualization, guided imagery and repetition of vocabulary with the use of visual aids and images can also support development of language and vocabulary (Hardy, 6 Benefits of Yoga for Children with Autism, 2015).

Not only can the practice of yoga bring more awareness to social cues such as facial expressions, actions and social behaviors but it can also bring more awareness to children’s emotions and how they are feeling. Because children with ASD often have difficulty with expressive and receptive communication, they may act out their emotions in unexpected or inappropriate ways. Breathing strategies can be taught to children with ASD in order to release difficult or uncomfortable emotions such as anger, frustration or anxiety in more healthy and constructive manners. Providing an outlet for children with ASD to express their emotions gives them the message that it’s OK to feel these emotions and when expressed constructively can support them in feeling better emotionally (Hardy, 6 Benefits of Yoga for Children with Autism, 2015).

Every time you breathe, your body makes a slight adjustment via the autonomic nervous system, The inhalation is “energizing and sympathetic.” Whereas the exhalation “is calming and parasympathetic.” The heart rate accelerates slightly with each inhalation, as the vagal brake exerts less inhibition of the sympathetic nervous system. With each exhalation, the vagal tone increases, slowing the heart rate, reflecting parasympathetic nervousness system dominance. This irregularity between heartbeats is known as heart rate variability (HRV) or respiratory sinus arrhythmia. Greater variations in the rhythms correspond to a more responsive autonomic nervous system, a general sign of good health. Controlled by the autonomic nervous system, these changes occur without our awareness or conscious participation (Goldberg, 2013, p. 48).

Think of a child slumped at his desk: His breathing is likely shallow and superficial. Consider a child on the autism spectrum whose elevated cortisol level may result in accelerated rates of respiration. How might their emotional states change if they deepened or slowed down their breathing? According to research by (Philippot, Chapelle, and Blairy), breathing patterns accounts for 40% of the changes in a person’s feelings related to anger, fear, sadness, and joy. In a 2011 analysis of yoga therapy in the treatment of psychiatric disorders, found yoga breathing an outstanding therapy in treating anxiety and post- traumatic stress disorder.

Changes in respiration alter emotional responses. Breathing at a rate of five to six breaths per minute, “coherent breathing is a safe and easily accessible method to reduce anxiety, insomnia, depression, fatigue, anger, aggression, impulsivity, inattention and symptoms of PTSD…it has no adverse effects and can be used in children (Goldberg, 2013, p. 71).

60 seconds 6 seconds on inhalation + 6 seconds of exhalation

Creating an Assessment

Yoga is also therapeutic when used as an adjunct to an existing form of therapy such as physical, occupational, speech, or behavioral (Goldberg, 2013, p. 6). When working with children, your first responsibility is their safety, you need to know if any position or activity could cause harm. Collect as much information as possible from the child’s parents, school, teachers, and therapist. In addition, to interviews use the parent questionnaire in appendix 1, which can be adapted for other professionals. Initially you will need a parent’s written permission and child’s medical history. Information about his cognitive, physical, emotional, and behavioral challenges, as well as learning styles, is important in determining your instructional approach. This information will help you determine whether to work with the child privately or with other children. It’s important that children are grouped in a way that is conductive to learning together and interacting safely (Goldberg, 2013, p. 8).

When you meet with child observe his physical limitations or discomfort. Does he respond to you words or gestures? Notice if he watches you when you speak. Can he imitate what you do? How close to him do you need to be to catch his attention, and how long can you keep it? Does he seem interested in what you are doing? Is he aggressive or anxious?

Determine if the child can sit comfortably in a chair. Can he sit on the floor cross-legged, on his feet with knees tucked beneath him, or with his legs straight in front of him? Can he sit up independently or does he need assistance?

What do you notice about his breathing? Is it fast and shallow? Rhythmic and deep? In the belly or chest? Is it through his nose or mouth? Does his respiration speed up when he moves quickly and slow down when he steps? Can he follow instructions about breathing in and out? Are there physical conditions from his medical history that prohibit movements such as forward or backward bending, twisting, lowering the head below the heart, or putting weight on a joint? Does he seem uncomfortable (Goldberg, 2013, p. 8)?

Teach to their Strengths and Learning Styles: When leading trainings on yoga for children and adults with ASD, I talk a lot about the need to speak their language and use their interests, strengths, and specific learning styles as tools for teaching and reaching your students. The most important and effective tool for you to cultivate is connection and understanding. When your students see that you are meeting them where they are (rather than expecting them to meet you where you are), they will be more open and willing to trust you and let you into their world (THORNTON, 2017).

For yoga therapy , its useful to obtain extensive information about the child’s history and predisposition. Knowing the child’s preferences, learning styles, strengths, and limitations informs every yoga therapy session. Visual guides, for example may be necessary for a child with ASD for follow directions. While a child with ADHD may respond to detailed instruction in a posture, the same information could frustrate a child with developmental delays. Long, focused periods of quiet breathing or the use background music may calm one child and agitate another individualizing instructions is essential (Goldberg, 2013, p. 5).

Set short-term goals and long-term goals. The children that improve the fastest are the children of families that implement and carry over the skills learn in therapy to the home (LITZY, 058: Occupational Therapist Rayne Pratt, 2012).

How to Create a Protocol

Before implementing the benefits of yoga therapy in your program, here are 10 guidelines for working with exceptional children.

- See the whole child

- Make yoga therapy fun

- Ahimsa. Do no harm

- Maintain your enthusiasm—this one can challenging

- Teach what you are comfortable doing

- Take Nothing personally

- Satya: Be yourself

- Plan to be surprised (Kiana scary cats, Diego believe in god)

- Know when to walk away

- Keep it positive (Goldberg, 2013, p. 28).

Learning requires trying something new or in a different way, experimenting with unfamiliar. The child who puts himself in your hands must feel certain that he is protected, secure, and safe. Not feeling safe triggers the amygdala, generating anxiety.

Additional things to keep in mind when creating a protocol are:

- Creating a sacred space requires being present for the child. That means attuning yourself to his wants, needs and potential sources of discomfort and adjusting your environment and expectations (Goldberg, 2013, p. 83).

- Creating a mood: dim lamp, soft music, photographs of sleeping animals, beautiful sunsets (Goldberg, 2013, p. 84).

- Expressions, voice, and breathing: strain in your face may come across as judgment. A deeper pitch in your cueing, softer volume, and slower pace create an atmosphere of acceptance (Goldberg, 2013, pp. 84-85).

- Lighting: Turn off as many lights as you can or use a lamp with a dim or soft colored bulb. In other cases, some children may be uncomfortable with darkness (Goldberg, 2013, p. 85).

- It’s important to distinguish between a child’s will and her needs, so that taking a walk is not a reward for screaming. If the child’s response becomes a battle of wills, you probably need to endure the screaming. In most cases, once the child realizes that she cannot bring about the desired change, she will adjust. Otherwise, the inappropriate behavior is rewarded and repeated (Goldberg, 2013, p. 86).

- Joy Bennett of Joyful Breath Yoga Therapy also recommends instrumental music, but “nothing too loud or too stimulating. Tibetan bells or singing bowls” have great resonance; children are soothed by their rich sounds and tones.” Joy stays away from children’s music. Autistic children often find it too loud and it aggravates them” (Goldberg, 2013, p. 87).

- When using yoga mats, position them in the floor before the children take their seats. This minimizes their preoccupation with placement of the mat (Goldberg, 2013, p. 90).

- Some children become anxious when asked to remove their shoes or to sit on the floor. To avoid contributing to their discomfort, you may conduct yoga therapy in your office or classroom seated in chairs, with or without shoes (Goldberg, 2013, p. 91).

- Examine your space from the perspective of one who sees all the details and is easily distracted from the “big picture”. In yoga studio, move props, pillows, bells, and drums out of sight before beginning class. Resisting the impulse to touch or play with instruments during class adds an unnecessary distraction for many children. When teaching in a classroom, move the desk to one area to create an open space. Remove books and games, cover or hide computers from view. After lunch or snack time, clean the area before seating children on the floor. Remember, one stray potato chip can become the source of preoccupation for some individuals (Goldberg, 2013, p. 92).

- Your selection of routines and poses help you maintain control. For example, you might begin with seated postures only. It is common for children especially those on the autism spectrum, to become distracted while transitioning from one posture to another. Sometimes, when a child stands, he runs. By selecting posture where children remain seated on the floor, you may feel more confident in controlling your client or group (Goldberg, 2013, p. 93).

- The length of the session has an impact on the child’s ability to attend and stay focused. Expecting a child to sit or follow directions for period beyond his capacity often leads to outburst or meltdowns. I usually recommend 30-minute classes, but that can and should be adjusted for comfort and control (Goldberg, 2013, p. 93).

- In yoga therapy, adults and children are literally eye-to-eye. Placing yourself on the level of the child rather than hovering above can mitigate anxiety and increase receptivity (Goldberg, 2013, p. 97). Ex: Temple Grandin “down low to the ground”

- In yoga therapy, you give instructions (auditory), demonstrate (visual), assist students as they move in and out of poses (kinesthetic) and touch or tap them gently in posture to direct their awareness to muscles that need to be activated or released (tactile) (Goldberg, 2013, p. 98).

- To begin your class seated on the floor, you need a term for this position. Choose a phrase that the children will recognize: cross-legged, crisscross applesauce, seated pose. Once children respond to this phrase, use it consistently. The same is true for all of the starting positions and postures names (Goldberg, 2013, pp. 102-103).

- Many autistic students have a problem with sequential memory and organization of time, a schedule can help a student organize and predict daily and weekly events. This lessens anxiety about not knowing what will happen next (Goldberg, 2013, p. 107)

- Simplify your language by choosing the smallest number of words needed to express yourself. Avoid nuance and say precisely what you mean. (Goldberg, 2013, p. 109).

- "A typically developing child will process pitch contours very precisely," Kraus says. "But some children on the autism spectrum don't. They understand the words you are saying, but they do not understand how you mean it." (HAMILTON, 2017)

- Viewing the cue card images rather than having to focus on a human instructor may be less uncomfortable for these special students, Lee explains.” The clearly drawn images, in shades of grey, lacking specific facial features, are preferable to photographs for similar reasons” (Goldberg, 2013, pp. 112-113).

- Firm, steady pressure can be calming to individuals with extreme tactile sensitivity. Children who seek stimulation or relief by hitting or pressure their heads into a wall may benefit from postures that increase pressure against the crown or fore head. Yoga therapy offers an alternative behaviors that is appropriate, non-injurious and within their control (Goldberg, 2013, p. 130)

- To help children learn how to refuse touch appropriately, let them practice in a posture. With their permission while they are in baby pose, begin a back massage. When they say “Stop Please” or use a hand signal, you immediately stop the massage. If they want you to resume, they signal or say “more please” and you oblige. Practice this frequently so they become comfortable saying “Stop” or “More” (Goldberg, 2013, p. 131).

- Make few corrections, but offer lots of assistance. There’s an important distinction. Assisting a child provides relief from discomfort and an experience of support in posture. Corrections about form are not generally beneficial. A child who struggles in many areas hardly needs another source of criticism. Strive to elevate the child’s self- esteem as well as his self-awareness (Goldberg, 2013, p. 138).

- Choose poses and breathing strategies at first that allow the child to feel successful and practice them consistently before adding new poses and breathing strategies (Hardy, 6 Benefits of Yoga for Children with Autism, 2015).

- Create a yoga schedule with pictures of poses so there is consistency and the child knows what to expect (Hardy, 6 Benefits of Yoga for Children with Autism, 2015).

- In the United States, public schools maintain the separation of church and state. For this reason, I do not recommend chanting “Om” or any other Sanskrit words or prayers (Goldberg, 2013, p. 208).

- Goldberg now uses the name "Creative Relaxation," and takes yoga poses and applies them to challenges that children have in either their school or everyday lives. This program is applicable to all children and ages, as it is just another form of movement involving exercise, mindfulness, and breathing (BRANDSTAETTER, 2014)

- Praise effort not ability or performance (Hardy, Montreal International Symposium on Therapeutic Yoga, 2017).

Conclusion

As previously stated, Yoga Therapy taught in an accessible way offers many benefits for children with autism. As autism diagnosis stays on the rise, chances are that we as yoga professionals will work with children on the spectrum or adults on the spectrum. Understanding how it feels to be someone with autism is the key to working with this demographic. Once we are equipped with knowledge of the population we can then focus on assessing and implementing protocol that brings the practice to where each child is at. Each case will be different and the sensory integration protocol will vary greatly from child to child but what stays the same is our attention to details and our willingness to teach from our hearts.